The Ladies Who Led

March 31, 2022

Bridget Foley

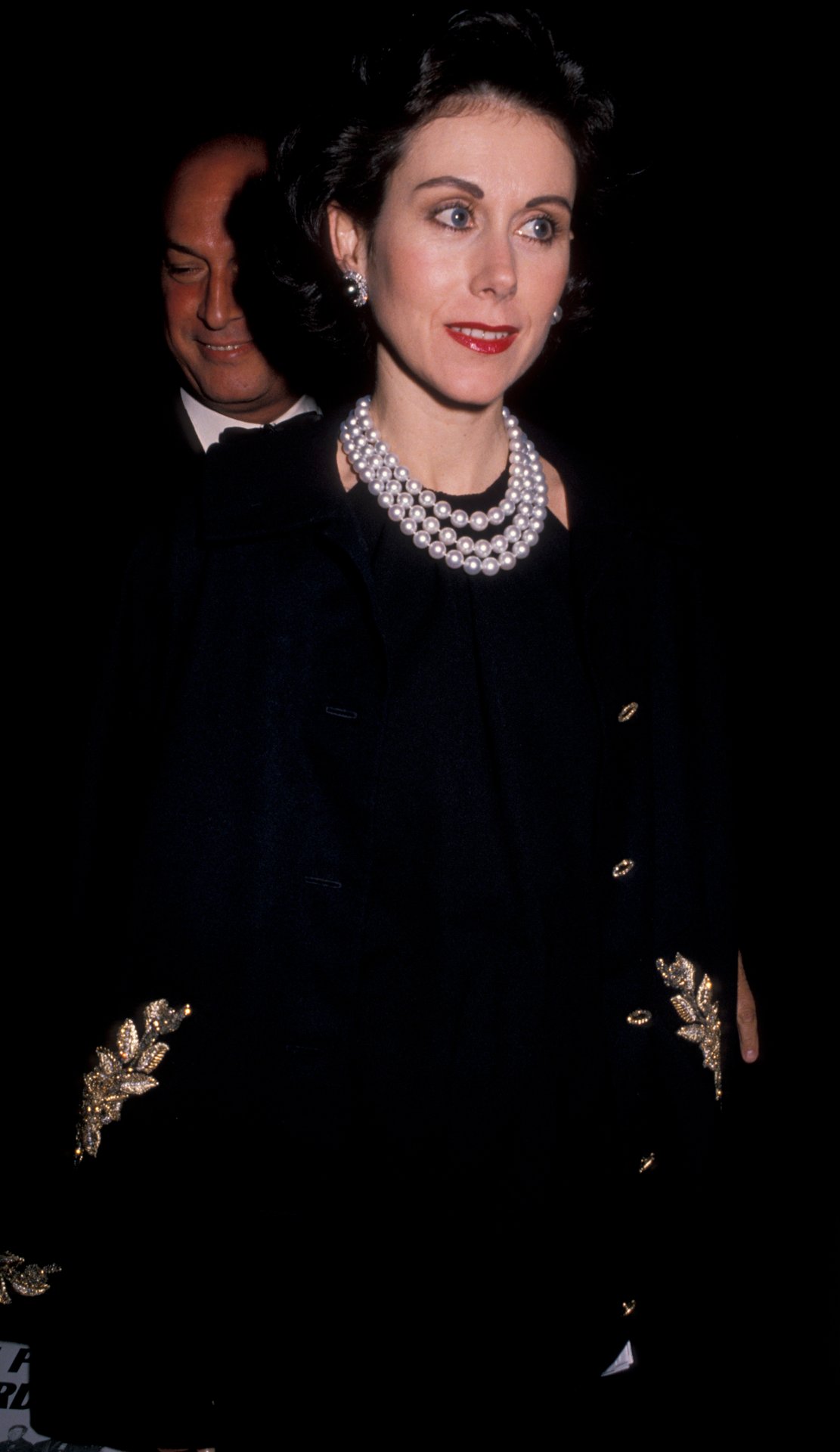

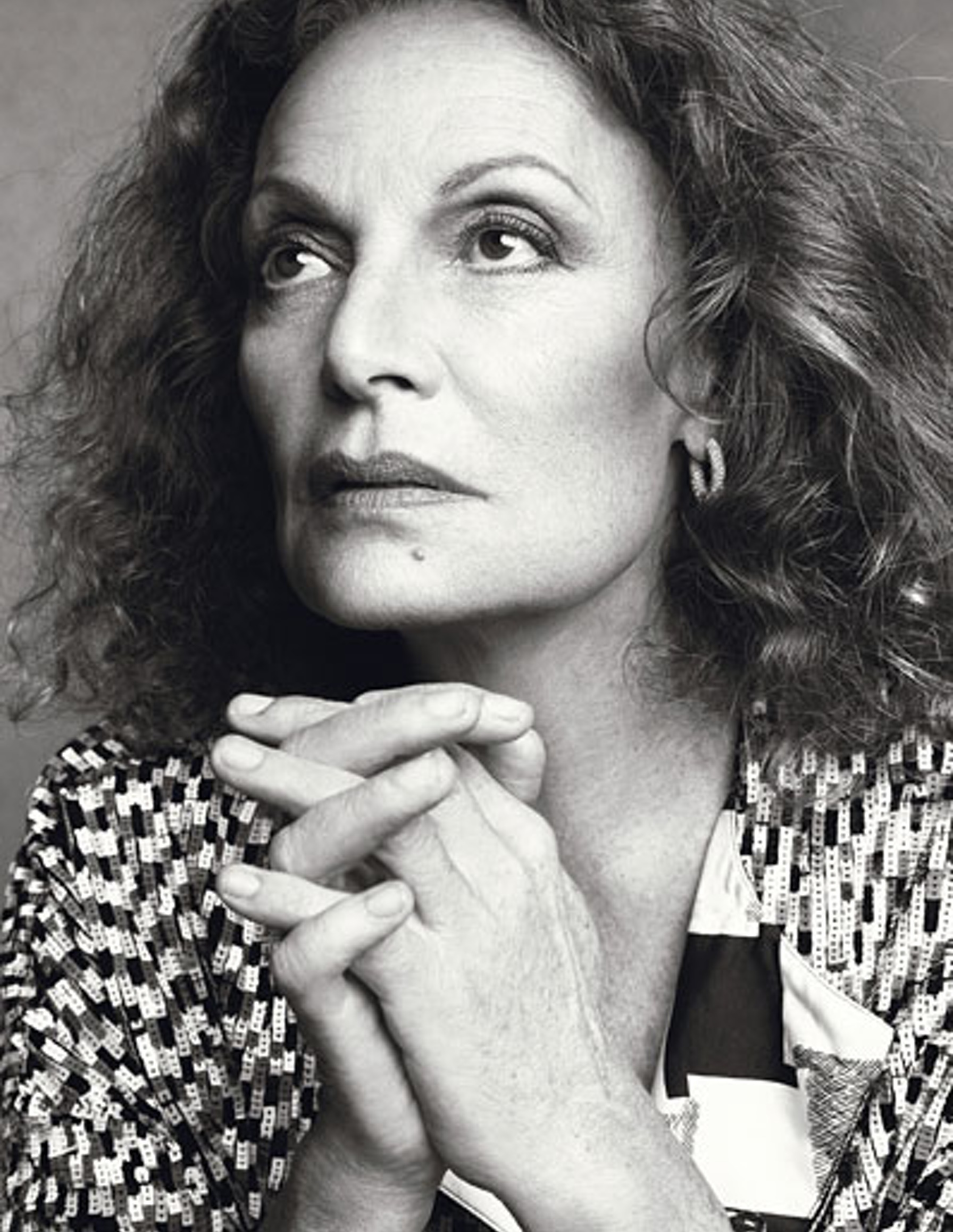

The CFDA has had 11 presidents in the 60 years since its founding. Three were women, each of whom left an indelible mark on the organization and industry. Mary McFadden and Carolyne Roehm presided briefly, at critical moments for fashion. Diane von Furstenberg served for 13 years, proving ever kinetic, sometimes in response to shifts in fashion and the culture, and sometimes leading those shifts.

That an organization founded by a woman, the indomitable Eleanor Lambert, has been helmed by men for most of its lifespan speaks to the issues of sexism and lack of diversity with which the industry, like the broader culture, has started to grapple. The irony is not lost on the women presidents who salute Lambert for her audacity and foresight. “You cannot talk about the women of the CFDA without mentioning Eleanor Lambert,” says von Furstenberg. She calls the groundbreaking publicist “a force, a visionary. The American designers were hidden in the back offices on Seventh Avenue. She pulled Oscar and Bill and Jim Galanos into the limelight.”

Lambert was McFadden’s publicist. “She was a very powerful woman,” McFadden recalls. “At that time, there was no one else.” Lambert was not someone to whom one easily said no. So when the PR doyenne strongly urged McFadden to accept the presidency, there was only one answer.

McFadden embraced the role she assumed in 1982. She presided over an intimate CFDA, conducting meetings at her studio at 240 West 35th Street (later formally dubbed the Mary McFadden Building). The designers would encircle her big wooden desk; at the time, they were a small group, with virtually all members hailing from the luxury sphere. McFadden doesn’t remember all who turned out for those meetings, only that “most of them are dead.” The CFDA opened its first office in 1985, but the habit of holding meetings at the president’s office continued into Roehm’s tenure, when the seat of power shifted to her desk at 550 Seventh Avenue.

McFadden maintains that, while Lambert founded the organization, she did not back up her grand mission to promote American fashion with concrete processes and marketing plans – a surprising assessment, given her undisputed position at the pinnacle of inventive PR. Rather, Lambert ran the business side of the organization. “I brought my organization into the fold, and from then on we started to develop ideas of how we should promote ourselves,” says McFadden, while lauding Lambert’s talent for networking, even if that term for the professional schmooze was not yet in common use. “She gave nice parties and luncheons, and she introduced us to everyone.”

Within that scenario, a group dynamic emerged, and designers began to think of themselves as part of a larger whole. In the nearly four decades since, some internal conflicts have occurred and factions developed, an inevitability as membership expanded to include designers of more varied perspectives. But at the time, McFadden stresses, “of course, everyone got along.”

While McFadden homed in on developing a structure and practices for the CFDA, Roehm’s two-year tenure from 1989 to 1991 focused completely on one devastating theme: AIDS. She assumed the office eight years after the disease was first identified in the United States, and seven years after the CDC named it Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, with the acronym AIDS. It had claimed countless members of the fashion industry, including the brilliant designer and recent CFDA president, Perry Ellis.

Against that backdrop, two industry giants championed Roehm’s candidacy — Bill Blass and her former boss Oscar de la Renta. “I was their girl, their choice,” Roehm says. She didn’t accept immediately. She had grown tired of sitting in CFDA meetings when people would “‘blah blah blah’ about AIDS and doing some sort of benefit,” and nothing would happen. “I’m a down-to-earth Midwesterner. Talk is cheap; it’s actions that matter,” she says. Roehm put a condition on her candidacy: She would spearhead a major AIDS benefit, and the membership’s “heavy hitters” would have to get behind it.

Roehm wasn’t alone in her resolve. Donna Karan had long pushed for such an event and was instrumental in making it happen. In realizing the fund-raiser, challenges abounded. “We wanted to sell clothes. You needed people who knew how to do that.” Roehm states an obvious point which would be central to the benefit’s success.

Designer vertical retail in the U.S. was still nascent, and few houses had a clue how to handle it. A major exception: Ralph Lauren. He got his firm’s president (and later vice chairman) Peter Strom, involved, which proved incredibly helpful. At the same time, Karan’s innovative contemporary DKNY collection was a smash hit, and a major resource at Macy’s, giving her “the clout” to approach the retail giant’s CEO Ed Finkelstein. “I’ll never forget what he said to Donna and me,” Roehm recalls. “‘Any time designers want to sell, I’m privately against it. That said, I’ll do whatever I can.’ He was a stand-up guy.”

Anna Wintour also wanted in. She brought on board event planner extraordinaire Robert Isabell, star photographer Patrick Demarchelier, and Si Newhouse who, Roehm says, gave the money “to get the whole thing rolling.”

Held at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, Seventh on Sale opened with a star-studded gala preview on November 29, 1990, and ran for three days. It featured about 90 designer shops and raised $3 million for AIDS research.

Carolyne Roehm

Upon its completion, Roehm decided one term as CFDA president was enough. “I had a midsized business to run,” she says. Decades later, the import of the event still resonates – for the money it raised, for the unity it fostered among CFDA members and for the light it shone on a plague whose victims had too often been vilified and forced into secrecy. “I’m proudest of this, for sure,” Roehm says. The CFDA Awards were a nice thing. But that’s clapping ourselves on the back. That’s not helping anybody.”

After Roehm, the CFDA shifted from its long-term norm of short-term presidencies. Stan Herman held the position for 15 years before von Furstenberg stepped up in 2006, serving, first as president and then as chairman, until 2019. She governed through an extraordinary time for American fashion. Under her watch, the CFDA guided its members through triumph (the ascent of a generation of young designers who achieved recognition on the global stage) and tumult (the major reset forced by the financial crisis of 2008/2009).

Diane von Furstenberg

Von Furstenberg approached the position with gusto and glamour. “I was the front; I was the cheerleader. I was the person who speaks the languages, who could talk to Ralph Toledano in Paris and the Italians in Italy,” she offers. Yet she stresses that she worked in constant partnership with chief executive Steven Kolb, whom she credits with doing “all the heavy work.”

Her tenure saw the launch of the Health Initiative to ensure proper treatment of models as well as the establishment of the Fashion Law Institute in partnership with Fordham University. Again, she deflects credit. “Steve does all the heavy work, so Steve gets all the credit,” she maintains.

That said, von Furstenberg acknowledges formulating a grand vision for the CFDA. Under her watch, its ranks expanded greatly. “I was very inclusive. My goal was to turn the CFDA into a family. I think I achieved that. I was the mother. That’s a role I can do well.”

One role among many. Von Furstenberg applied her considerable skills to far-flung endeavors. Her fund-raising efforts included the creation of a flag modeled after the Stars-and-Stripes. For $50,000 each, designers could buy and name stars. And she spearheaded the publishing of several books, including one called “Impact.”

She sought not only to increase the global profile of American fashion and its individual participants, but that of the CFDA itself. “I wanted the world to know what those initials stood for,” she notes. “I am informal; I am cozy. I invite people, and I make people feel good. One of the things I know how to do is connect.”

Two people von Furstenberg connected: Kolb and Wintour. I told Steven, “You have to know Anna.” Wintour became increasingly active in CFDA initiatives, meeting monthly for breakfast with von Furstenberg to discuss ideas. The CFDA Vogue Fashion Fund had existed prior to von Furstenberg’s presidency, but, she says, “I think I amplified it a lot.” This included creating a Paris showroom for the fund’s participants during fashion week there, increasing their profiles and bottom lines.

Another program, Fashion’s Night Out, developed in response to the financial crisis. The idea was to get people shopping again with a night of special events and celebrity appearances. For the inaugural effort, across New York City on September 10, 2009, more than 700 stores participated. The concept ultimately became an international event, lasting for several years, before, von Furstenberg muses with wry detachment, “it became very crazy.”

Von Furstenberg acknowledges that over time, her role turned “a little complicated.” As the digital age changed the way we all live and experience media, she came to believe that the fashion calendar – shows six months in advance of their arrival at retail – “was a little bit odd.” The CFDA thus commissioned the Boston Consulting Group to conduct a study on best practices for the future of American fashion. The findings were broad and non-specific. “Then I realized that it’s not fair, and it’s not right to impose on others my doubts and my wanting to change things,” von Furstenberg notes. In a nutshell: “Everybody could read the report and decide to do whatever they wanted.”

Today, von Furstenberg treasures her relationship with the CFDA. She never intended to stay as long as she did. Initially, she anticipated a two-year run, and then accepted “another and another. Before you know it, it’s 13 years. It was great fun. It was very much a family. Absolutely, I’m very happy I did it.”

Now, from outside the CFDA’s inner sanctum, von Furstenberg still believes strongly in the organization’s purpose. “The members should feel that they’re part of something– it should still be a family,” she says. “It should address important issues, sustainability and all of those things. It has a lot of value. I hope I was a catalyst.”

As for her predecessors, Roehm no longer pays much attention to fashion. Years ago, she shifted her attention to other creative pursuits. She has written numerous books on interiors and gardening, and designs products for the home, available on her website.

Conversely, McFadden still follows fashion closely. “Who doesn’t?” she quips. She is proud to have been involved in establishing the CFDA as “something that is so important today.” And she loves current fashion. Asked what she finds most compelling about it, she responds instantly: “Its freedom.”

MCFADDEN/ROEHM PHOTOS BY GETTY IMAGES; VON FURSTENBERG COURTESY PHOTO