Bill Berkson was the kind of poet who wrote the term “Garbo’s awning” to signify which Manhattan river he was referencing in his poem The Obvious Tradition. Another poem, Accounts Payable, ends: “Hours where money rinses life like sex, Whichever nowadays serves as its signifier.”

Signifiers, money, sex, payable accounts, mysterious awnings abutting known rivers. There is something redolent of the fashion world in all that, a sumptuous leitmotif of ledgers and legendary glamour. The poet’s mother, fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert, a Presbyterian from Indiana, was predestined to be a legend herself. She not only gave birth to such a poet but also to traditions within the fashion world that have become obvious in its need for them because of the spheres of business and style and celebration that orbit around such a world.

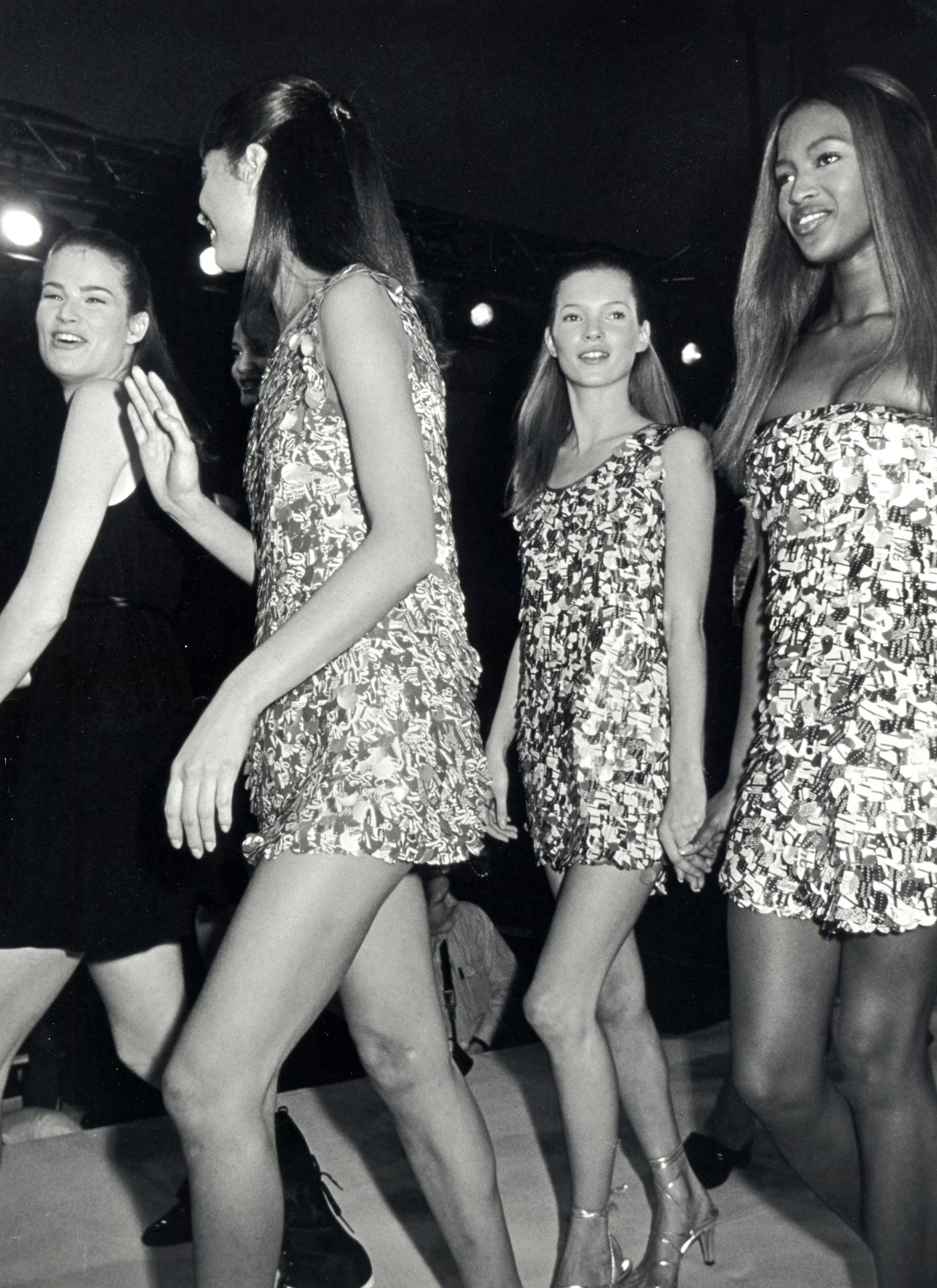

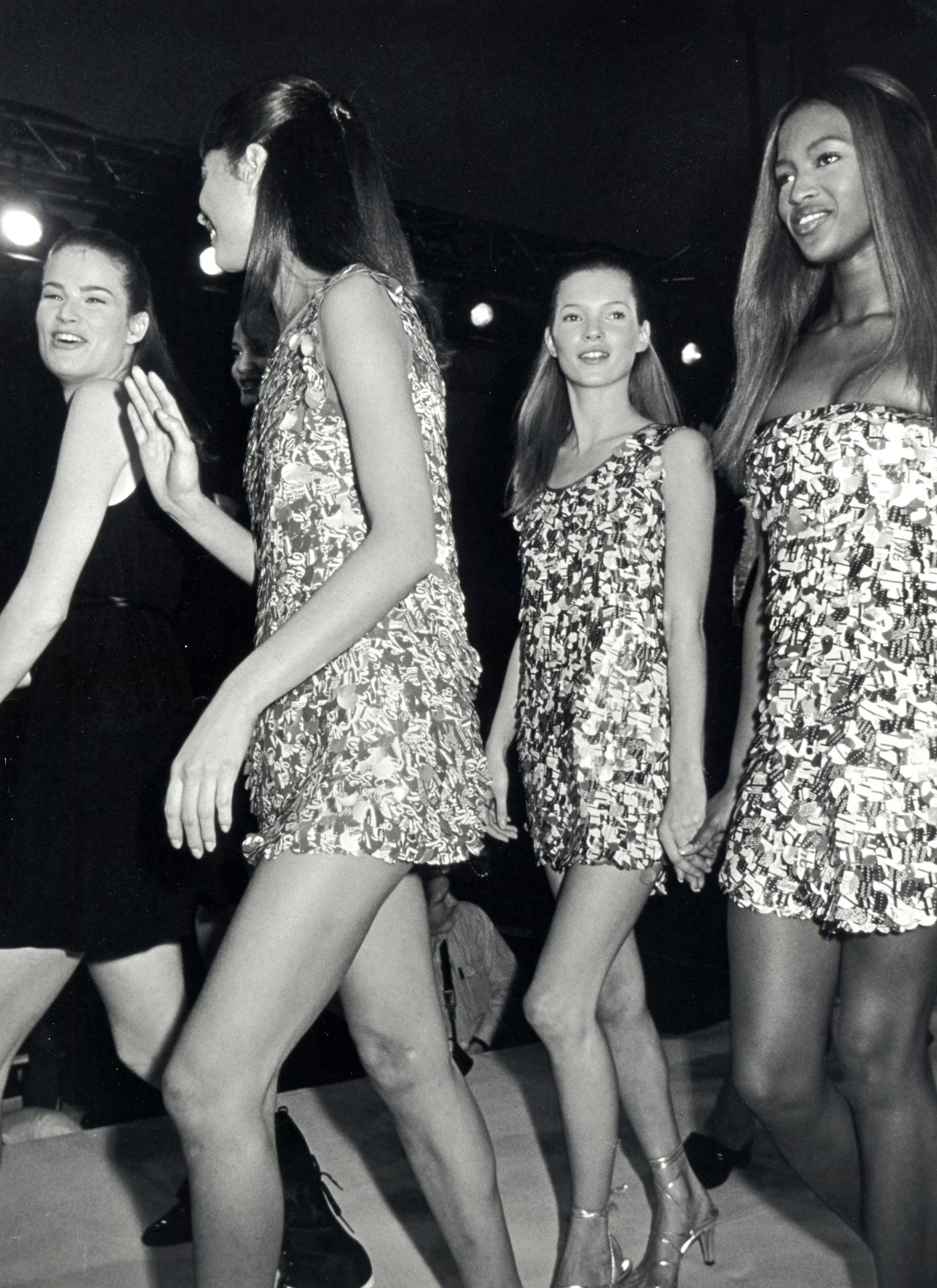

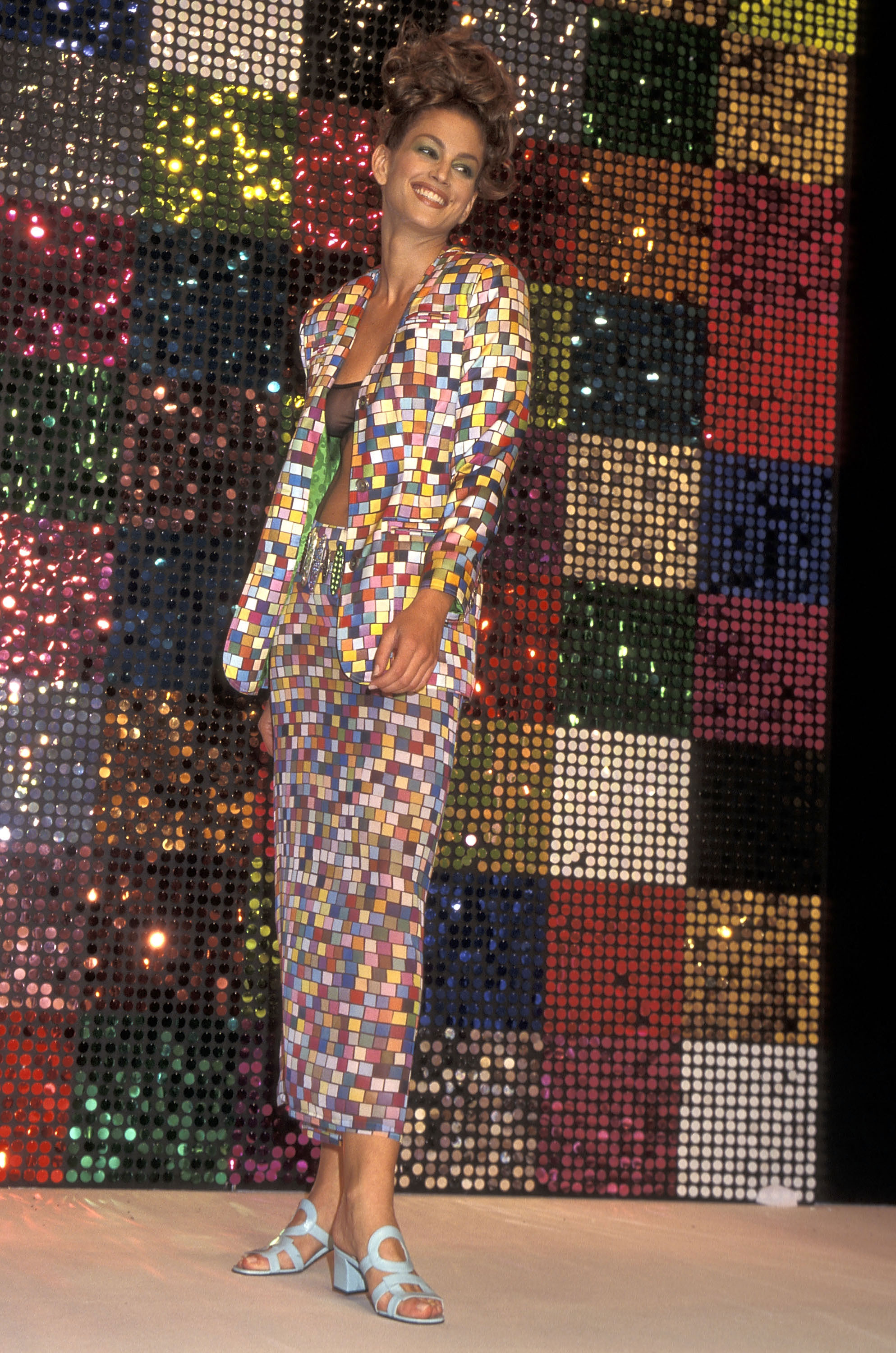

Lambert created the International Best Dressed List. She came up with the idea for the Met Gala for the Costume Institute. She invented New York Fashion Week. Each is, yes, a signifier of Lambert’s well-honed instinct for spotting the obvious need for each of those things and then paring all the obviousness from each and replacing it with a kind of knowing, needy magic – for what is fashion if not the knowing marriage of just that: need and magic?

According to Amy Fine Collins, who wrote about Lambert for an April 2004 edition of Vanity Fair, the deeply American fashion publicist “masked her brilliance behind what Cecil Beaton called the ‘halting’ veneer of a hayseed.’’ Hayseed? Not so much. But deeply American? Yes: that was her mission statement in a two-word pitch-perfect pitch. She moved to New York City after having studied to be a sculptor in Chicago. Again from the Fine Collins story: “Lambert juggled two $16-a-week jobs, one at a fashion newsletter, Breath of the Avenue, and another designing covers for a book publicist. During her free time, she’d eat at the Automat and head ‘to the Algonquin to study the crowd,’ Lambert said.”

“Studying the crowd” could also have been Lambert’s mission statement because her long career was based on giving her own American crowd what it wanted: more of itself but in a reconfigured, keenly curated way. Before Lambert created New York Fashion Week’s predecessor, New York Press Week, as a publicity arm of the New York Dress Institute, fashion was Eurocentric. But World War II, during which Paris fashion houses shuttered, offered Lambert an opening to highlight American fashion that aligned with the country’s patriotic fervor. In 1943, she founded Fashion Press Week in New York and was very mindful of displaying thoughtfulness to out-of-town journalists who felt welcome for the first time. She even arranged for them not only to get free tickets to see Audrey Hepburn on Broadway in Gigi by Anita Loos in 1952, but also to meet the star backstage. Before creating Fashion Press Week, Lambert had already carved out a niche for herself as a publicist for major artists, such as Salvador Dali, John Steuart Curry, Jacob Epstein, George Bellows, Isamu Noguchi, and Jackson Pollock, and even created the Art Dealers Association of America. She then set out to convince others that American fashion itself was an art form. But Diana Vreeland – the concave mirror image of Lambert during their days reigning over different realms in the same queendom – found Seventh Avenue nothing if not provincial and was having none of it at first. When Lambert told her about her idea for an American Fashion Week based on her love of her publicity clients in the industry on Seventh Avenue, Vreeland was incredulous and dismissive. Chessy Rynor, who chafed under Vreeland’s dictatorial edicts when she worked for her at Vogue, described Vreeland’s office stride as “toes first, head and neck on a backward slant like a camel.” When Lambert told her of her plans, Vreeland, at her most camel-like, slanted that helmet-haired head of hers backward and snorted, “Eleanor, you’re such an amateur.” It was one of her less cryptic proclamations, but in its specificity proved to be specious.

In 1962, Lambert went on to create the CFDA where her vision of fashion as an art form within the constructs of an industry is still part of the organization’s own mission. “For the first time in the history of American fashion, leaders from all branches of creative design across the country have banded together for the purpose of furthering the position of fashion design as a recognized branch of art and culture,” she wrote at the time.

Ruth Finley was another central character in the New York’s fashion week, responsible for diligently scheduling the shows for a pink Fashion Calendar. The CFDA acquired the Fashion Calendar in 2014 and took over the Official New York Fashion Week Schedule.