Before there was the COVID pandemic, there was the AIDS epidemic.

Back in the Eighties, AIDS generated at least as much dread and anti-science hysteria as Corona has done in the past two years. It was a then-untreatable illness and a fatal one. For fashion, despair was compounded by widespread homophobia.

A horrible tick tock of death took hold. In 1985, fashion lost designer Chester Weinberg. 1986, Perry Ellis. 1987, Willi Smith. 1988, Lee Wright. 1989, Isaia Rankin. 1990, first Patrick Kelly, then Roy Frowick Halston. It was, to say the least, a scary time.

But raw fear gave way to empathy and courage and Seventh on Sale was born. Like any birth, there was a gestation period and there was pain before there was joy.

Ellis was a star designer and the CFDA President when he fell ill. The disease had ravaged his skin. Donna Karan took notice. “I said, ‘Perry, what’s wrong?’” Karan recalled recently. “He said, ‘This is a private matter. I’m allergic to strawberries.’ I was shocked. Perry didn’t want the attention.”

Few people did; especially in fashion. Fashion was in the business of building aspirational brands, dreams of the beau monde. When designers or other influential movers were struck down by AIDS, their death was ascribed to something else – like pneumonia – if a cause was given at all.

“Most people did not want anything to do with AIDS. And they thought only gay people get AIDS,” Karan said.

Karan’s longtime public relations guru and confidante Patti Cohen remembered, “I didn’t know what was happening. Donna came to me and said, ‘Perry’s sick. We have to do something.’”

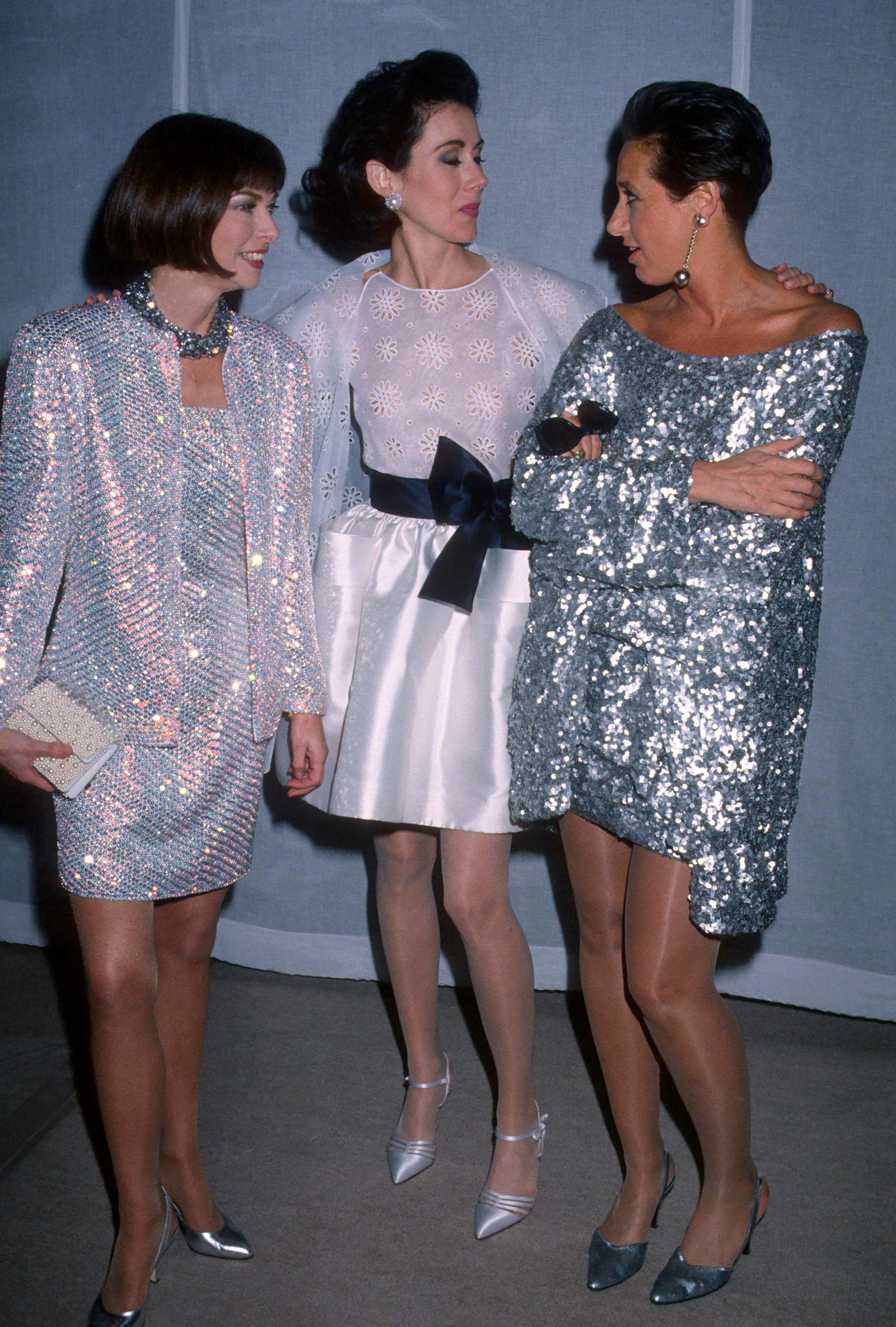

Unbeknownst to Karan, Anna Wintour and designer Carolyne Roehm – who had succeeded Ellis at the CFDA – and a handful of other leading designers including Ralph Lauren, Bill Blass, and Oscar de la Renta, were having similar conversations.

“I remember speaking with Donna, Marc, Michael, Calvin and Ralph, and deciding to do something together,” said Wintour. She doesn’t recall exactly who contacted whom when; but, she said, Karan and Roehm were reaching out to everyone to get support.

Recalled Karan, “Anna and Carolyne Roehm came to me and said ‘We want to do this thing.’ I said, ‘It’s everything I’ve been talking about with Perry.’”

The epidemic had touched close to home for Wintour, who, two years prior, had been appointed editor-in-chief of American Vogue.

“Everyone working in fashion in New York had friends and co-workers who were dying,” Wintour, now artistic director and global chief content officer of Conde Nast, said recently. “I lost a close colleague of mine from New York magazine, as well as the brilliant architect Alan Buchsbaum, a good friend, who designed the desk I use to this day. It became impossible to stand to the side.”

In the early 1980s, America watched the heartbreaking saga of Hollywood’s Elizabeth Glaser unfold. Glaser went public with the fact that she had caught HIV/AIDS through a blood transfusion and transmitted it in utero and at birth to her two children, one of whom died. (Glaser herself eventually succumbed to the disease in 1994). Meanwhile, Elizabeth Taylor had thrown her unmatched star power behind the scourge, devastated by the death of closeted superstar Rock Hudson in 1985. That same year, she chaired the Aids Project Los Angeles (APLA) gala.

Karan turned to what she knew best: reaching the customer through shopping, she said. “I thought, ‘how do we engage the shopper? How do we engage the industry?’ We should open a store.” Fashion, thought Karan, was a great way to get people’s attention.

So the idea was born to create a fundraiser around shopping. Stores, who might have seen a threat to their business, were supportive, Karan said.

The first Seventh on Sale was a four-day event at the Lexington Armory in Manhattan with Karan and Ralph Lauren as co-chairs.