While you’ve been an advocate and catalyst for discussions about gay Black men throughout your career, what specific event or inspiration led you to launch your own platform, Native Son?

After handling digital at Essence, I became Editor at Large, responsible for booking talent for covers, festivals, Black Women in Hollywood, and social media exclusives. However, when Time, Inc. and Warner Bros. separated, I was laid off along with over 700 others. I called Barbara Biziou my vision coach, to tell her that I was let go.

I had never been fired or laid off, nothing of the sort; I was gagging in my Saint Laurent suit. Barbara said, “Congratulations, the universe gave you what you asked for. You’re now free of your corporate job, you have money as part of your severance package, and you have time.” The next significant thing that happened was Bevy Smith saying, “Own that you were laid off, tell people, celebrate it, and broadcast it.” That gave me this opportunity to not have any shame around it.

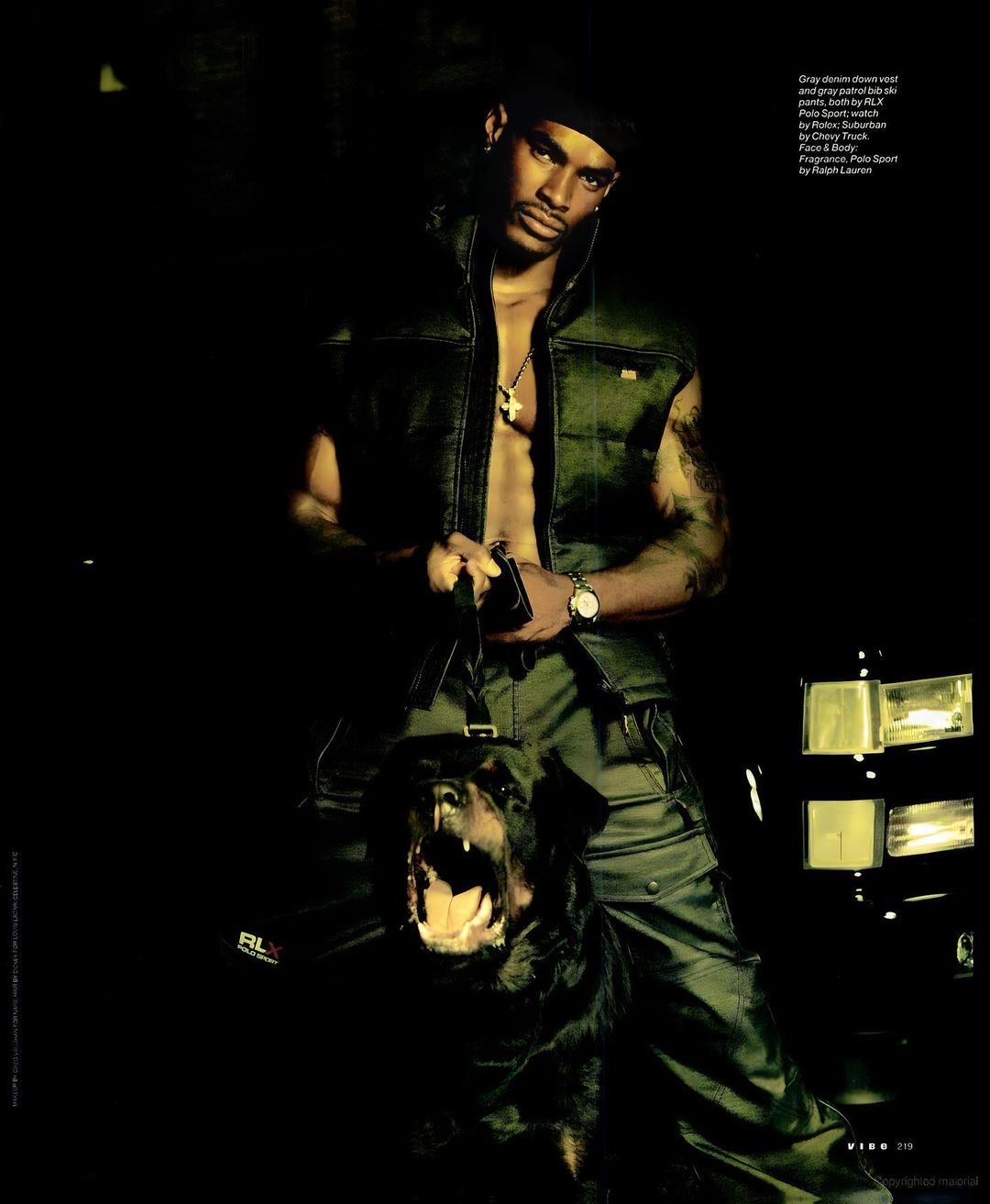

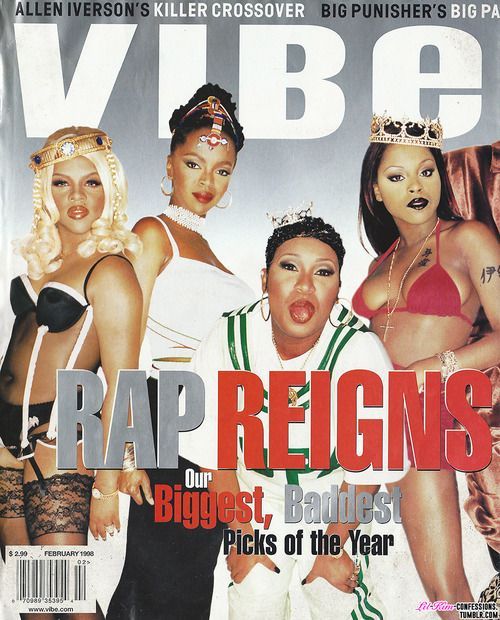

I took a trip to India to visit Punit Jasuja an ex-boyfriend; I extended my stay from four weeks to six and had an “Eat, Pray, Love” experience. I even wrote a cover story for Elle Décor India on his home during this time. While detoxing and journaling, I heard a voice that told me to focus on “Black Gay Men.” Reflecting on my privilege as an openly gay editor-in-chief of Vibe, I thought about the hardships individuals like James Baldwin, E. Lynn Harris, and Andre Leon Talley faced.

Realizing no platform represented our community, I decided to create one, leveraging my media and branding experience. I chose the name “Native Son” after spotting the book Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin on my bookshelf.

Native Son’s website states that it ” embodies a global platform that illuminates Black gay/queer men and assures them of their worthiness and purpose in all communities in which they exist.” Is it primarily about acknowledging the existence of these men, or does it encompass a deeper and more profound purpose?

Native Son is more than just a platform; it’s a movement and a community with a strategic vision. It aims to portray Black, gay, and queer men as beautiful, successful, loving figures and fathers, normalizing their existence. We’ve partnered with AARP, Amazon Music, Citi, Gilead, Google, HBO, Cadillac, Bloomingdales, Byredo, P&G, Morgan Stanley and Netflix. The goal is to build a like-minded community, showcase our achievements, support each other, and boost our confidence to navigate the world.

Inspiration for Native Son comes from two places: the support and celebration of Black women at Essence and the Black trans movement. Janet Mock, Laverne Cox, and other Black trans women who prioritize discussions about violence against Black trans women on the red carpet over fashion inspired the desire to be in the community in a similar way for Black gay men. Earlier this month, Native Son and Netflix spent an evening together at The Chelsea Hotel as we gathered for George C. Wolfe’s Rustin film based on Bayard Rustin.