Andre Walker, born in London and raised in New York, is one of fashion’s most enigmatic figures.

Entirely self-taught, he has spent more than four decades shaping ideas that reverberate across the industry while resisting its conventions. By seven, he was sketching compulsively; by fifteen, he was on television with designs championed by Patricia Field, who stocked his pieces before they were “market ready.” At eighteen, the New York Times profiled him as downtown New York’s boy wonder.

Prevented by his mother from attending fashion school, Walker enrolled at Brooklyn Technical High School, channeling rebellion into creation. His work surfaced first in the underground press—The Village Voice, SoHo News, East Village Eye, The Face—before reaching the mainstream through Details and The New York Times. Early champions like Bill Cunningham, Patricia Field, and André Leon Talley recognized his instinct to cut freehand, designing not from patterns but pure imagination.

Walker has produced fewer than a thousand garments over the years — a rarity in a field driven by volume. He calls this “underproduction,” a devotion to the unseen and to ideas distilled rather than amassed. Collaborations with Pendleton, Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, Virgil Abloh, and Kim Jones cemented his reputation, while his 2017 Pendleton collection, Non-Existent Patterns, drew on his childhood experiments and became one of his most celebrated works.

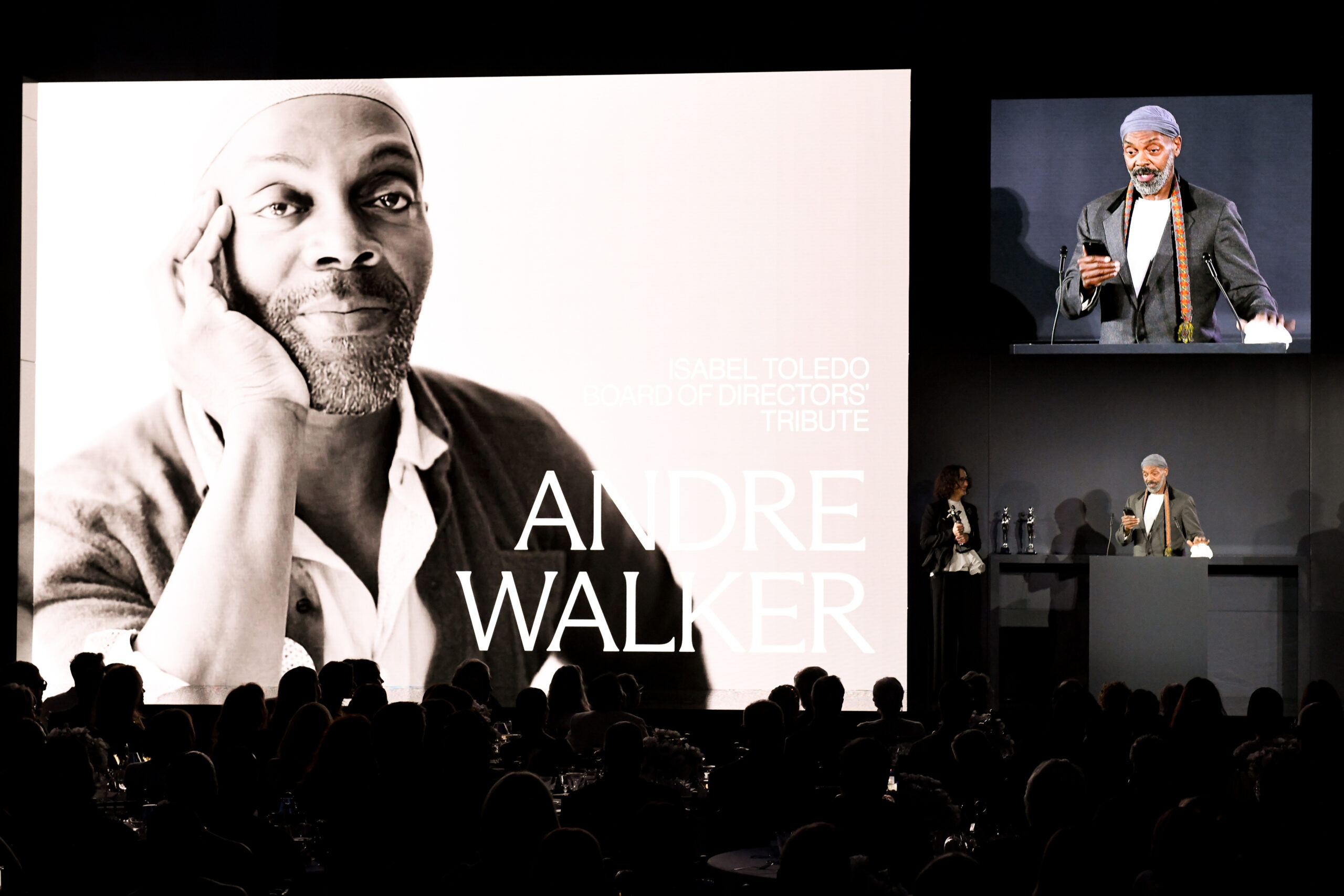

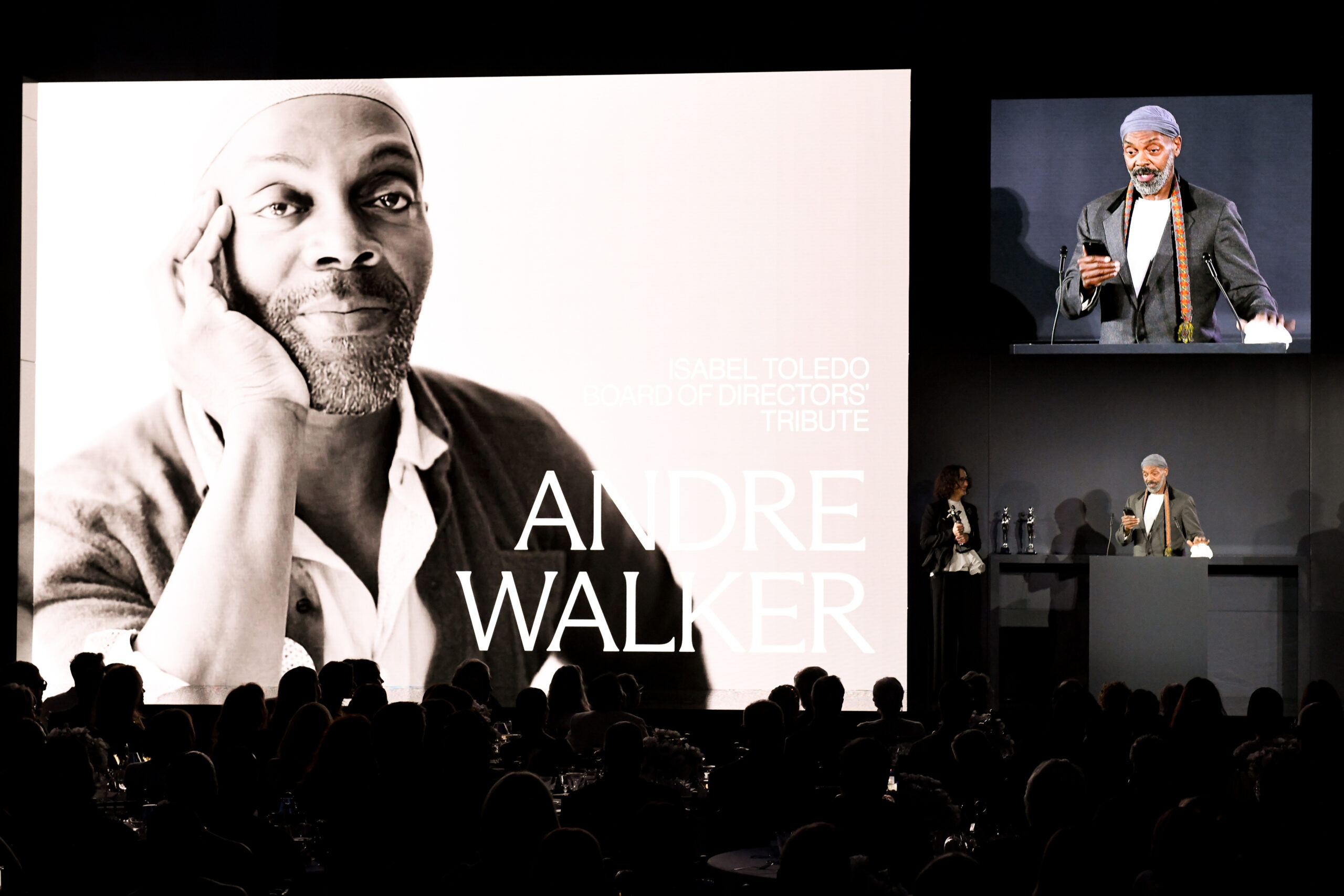

Walker has also sold original concepts to other designers, letting his vision ripple through their work. His contributions have been honored with the Isabel Toledo Board of Directors’ Tribute at the 2025 CFDA Fashion Awards presented by Amazon Fashion.

Though often described as elusive, Walker resists the label. “If I’m elusive,” he has said, “then I’ve failed—just look at all the press.” What defines him instead is curiosity and urgency: the need to sketch an idea the moment it arrives, to bring into being something never seen before.

Before the runways, collaborations, and mystique—who was Andre as a child?

My world began with headlines. As a boy reading fashion magazines, I was struck by words like ‘silk crêpe de chine blouse’ or phrases like ‘Paris is a Balloon.’ They weren’t just lines on a page—they were incantations. Beyond them lay whole worlds: Paris as the craze of glamour, or nostalgia for the 1940s. I thought, this matters. Pair those words with imagery and I was breathless. I knew I had to be part of this.

My parents, Caribbean immigrants from Jamaica, carried themselves with certain air (after emigrating to London). Being well dressed wasn’t optional—it was law. Mom shopped at Biba, Barbara Hulanicki’s iconic department store, giving me a front row seat to spectacle. My childhood was consumed by fashion—not as craft but as pure idea. I thought only about what people wore, not how clothes were made. It was constant discovery.

At seven, I was reading W Magazine, which shaped how I spoke. By my teens, I was devouring After Dark, Interview, French Vogue, and loads of other alternative international press/publications. Words, images, voices—they built my world. Gymnastics gave me freedom of movement, and racism, which I hadn’t noticed as a very young child, grew into something I despised deeply as I learned about it through experience and hazard.

At thirteen, fourteen, fifteen—what did the dream look like for you then?

The dream was singular: Paris. Everything radiated from it—the clothes, the lights, the music, the fashion shows. My mother refused to let me attend the High School of Fashion Industries or Art and Design. I spent a year at Samuel J. Tilden, which traumatized me, before moving to Brooklyn Tech. That resistance only sharpened my resolve. I sketched and wrote compulsively for years, following instinct more than plan. It took over a decade to truly understand my abilities.

Even my most recent collection felt like a tapestry woven from those early touchpoints, roots spreading in every direction. And all of it, without a degree or certificate, just working through trial and error, tunnel vision, supportive friendships and the connections they brought about.

You became visible early, first through underground press before the establishment caught on. What did that visibility mean?

My rebellion correlated with visibility. I was in the Times, East Village Eye, Village Voice, The Face. The underground carried me to the mainstream. Before the Times, there was Details. And around me were the people who mattered: Bill Cunningham, Patricia Field, Kim Hastreiter. They shaped my path and we’re mentors in a way.

You’ve described your process as “freehand fabric cutting”— more instinct than pattern, more improvisation than industry. Has that method ever failed you?

Sure… It’s unknowing. Think of folding a paper airplane for the first time. You rely on imagination—what you think it should look like, how it might fly. That uncertainty, that space between the imagined and the real, leads to the design. That’s the essence of creation: working inside the unknowing.

Of course, the industry pushed back. Being self-taught meant I wasn’t supposed to belong. But my ignorance only fueled the practice and my resolve to make things work. My truth is in the work, not a stamp of approval.

After Paris, you shifted course. Why did you leave—and what pulled you back to New York?

My last collection was shown in Paris in 2001. By 2003 I was mentally exhausted and admitted I needed a change. Things were so bad my friends Masha and Tyler called my mother and sister. I moved back to New York in 2004 and started living differently. I did some time working with Zac Posen and then started working with Marc, as his personal design consultant and soon after with Kim Jones in a similar way. This period also led to my first magazine project called TIWIMUTA — an acronym for This is what it made us think about.

This year, you attended the Met Gala with the Fear of God team—a space you’d avoided before. What changed?

The last time I was invited was during the vaccination proclamation. I had two garments in the exhibit, said yes, then decided against it. This year was about an invitation from Fear of God to attend. Jerry and I bonded over what I call my ‘Kill all Blacks theory’—total comedy.

My mother and sister told me, ‘If you don’t go, you’re an idiot.’ So, I went. The night felt dissociative. Traffic kept us stuck for over an hour; we arrived last. I didn’t know where to go or what to do—I only knew I was with the Fear of God ensemble. It clicked when we hit the carpet later.

Inside, the production was extraordinary. Stevie Wonder performed. Usher and Coleman Domingo commanded the room. Still, I floated in my own world, thinking, I want to meet Donatella Versace, I want to meet Jonathan Anderson. I barely saw anyone, though I did greet Donatella, who was gracious. In the end, I was honored, proud, grateful I said yes. It wasn’t just about the Met. It was about letting myself back into spaces I’d turned away from, loosening self-preservation, and saying yes to being there.

Also, knowing this was an Anna Wintour affair, made me see things less emotionally.

You’ve called fashion “a kind of utility,” but also spoke of loving the presence of presence. How do you balance the practical and the poetic?

Clothes are an undeniable utility. Balancing the practical and poetic depends on purpose, reason, impulse, and desire. Societal conventions and traditions play a part in the perception we have of all this and how we respond. The utility can be mental or physical, imagined or proposed. How it materializes is one of the wonders of self-actualization; seeing your thoughts and dreams come to life.

You’ve said you have no archive of your own—that luckily your friends held onto your past. What was it like to re-meet that work?

It was amazing. Seeing those pieces again made me realize people never had the full scope of my experience.

My last show—a collaboration with Pendleton Woolen Mills—was built from those rediscovered garments. It became one of my most successful collections: Spring/Summer 2018. I called it Non-Existent Patterns because each look traced back to childhood, when I’d lay fabric on the floor and cut directly, guided by instinct.

It was deeply experimental, almost primal—making clothing without a pattern. Revisiting it through others’ memories was both a reunion and a revelation.

We’ve talked about the past and philosophy, but what about now? What’s lighting you up today, and what might the next year hold?

The future is unfolding quietly but with intention. More to come with a focus on organization, primal resources, and structure. Assembling a team takes all the discipline and patience needed to make this work. My resolve is to keep calm, keep working, and carry on, honoring all the gifts and support that have sustained the work and me, with gratitude.

You just took home the Isabel Toledo Board of Directors’ Tribute Award at the 2025 CFDA Awards. How are you feeling?

How am I feeling? Wonderful. The award is such a beautiful one. I’m in awe with gratitude about this honor, the CFDA community, and being amongst such a set of winners.

Donatella, Ralph Lauren, Mary Kate and Ashley, et al. I asked myself why I was so emotional about this tribute and my answer is still finding its voice.

One thing is sure…There is more work to do, and I feel understood. What a true miracle this is. I’m a believer in every way possible. More to come and giant thanks to everyone who made it possible.

If you were remembered not for what you made, but for one question you kept asking the world, what would it be?

Why can’t we acknowledge the foundations of truth that sustain us all? People overlook those foundations constantly—and it’s typical of society to do so. But without truth, what are we really standing on? Do we know what “free-of-charge” truly means?