The Dream Will Never Pay Off

December 21, 2020

Draven Peña, Elie Fermann & Alexa Ream

This opinion piece was written by three students at The University of Cincinnati who published the Sustainable Fashion Initiative report. Please note, that the CFDA has a paid internship program and pays interns a minimum wage. We encourage our members and the industry to follow the same practice.

Unpaid internships have been a prickly subject for quite some time and yet the issue has gone largely unresolved. To many, unpaid internships are considered petty compared to fashion’s ‘larger’ challenges. As students, we must disagree.

The Problem, From Our Perspective:

The fashion industry as we know it, the industry that we as fashion students are being trained for, is collapsing.

When most people think of fashion, they think of the runways and the magazine covers. However, this image of fashion is only one side of the curtain — an aspirational facade of an industry that requires an overwhelming number of human and environmental resources behind the scenes. This facade is crumbling and has been for some time now. In her book, The End Of Fashion: How Marketing Changed the Clothing Business Forever, Teri Agins highlights how luxury brands no longer make money from clothing and how runways are not used to sell products; instead, they are used to sell a dream into which consumers will do anything to gain access. Agins points to the ways that this business model has destabilized the industry and has led many of fashion’s darlings down a path towards failure. Giulia Mensitieri’s book The Most Beautiful Job In The World: Lifting The Veil On The Fashion Industry reveals how the people who keep the fashion dream alive — the designers, stylists, photographers and interns — are faced with an increasingly precarious existence. In Amanda Mull’s article for The Atlantic, she questions whether the aspirations upon which fashion is built, the ideals that keep people working with no pay, are fading into history, saying, “Luxury fashion is built on the emotional scaffolding of human aspiration—what happens to the industry when everyone gets sick of worshipping rich white people?” A good question, to which we would add: What happens to those of us who work in fashion when the facade is no longer worth fighting to uphold?

We, the authors of The Dream Will Never Pay Off, are three students in our fourth year (of five years) within the Fashion Design program at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning (UC DAAP). As students who pay a hefty tuition bill every semester to be trained for this industry, we have experienced first-hand the dissonance between fashion dream and fashion reality. In fact, our 2022 class will pay $2,068,412.50 over five years for the expenses related to our internship experiences. Our courses explore the glitz and glamour that is still alive within the spectacle of fashion shows like Chanel’s Cruise 2017 collection taking place in Havana — essentially turning the fleeting runway moment into a full-fledged vacation for fashion’s elite. We look around at our contemporaries to see a majority female workforce and watch as the industry splashes feminist slogans across products, runways, and editorials; however, most of the designers we read about are male. We are taught that Fast Fashion is not actually fashion and yet we watch as companies like H&M and Zara give rise to billionaire dynasties with accumulated influence and demonstrated control over the structure of our industry. Sustainability conferences emphasize the size of fashion (whether that is the often misquoted levels of pollution or the fact that Fashion is worth $2.4 trillion), insinuating that fashion has the power and the wealth to change the world. Yet the reality of working in fashion seems to be void of wealth, empowered women, vacation time, and world changing opportunities.

For us, and for so many people working in the fashion industry, the question becomes: Will the dream ever pay off?

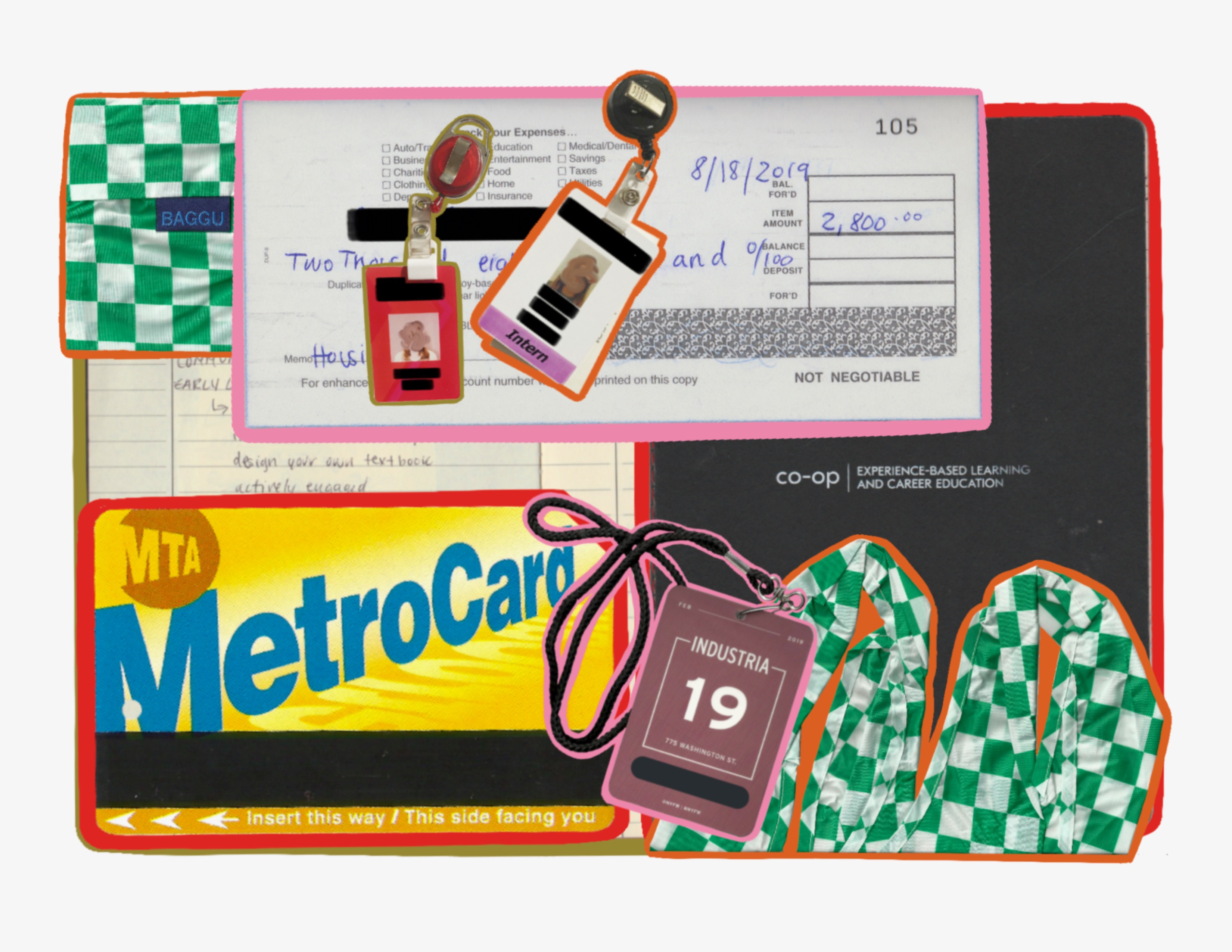

This question is not simply about our bank accounts. We do not believe it is productive to argue that pay reflects worth, but performing unpaid labor does reflect a system of exploitation. We have experienced this most personally through the unpaid internship structure that has been normalized across the fashion Industry. The companies we have interned for did not pay minimum wage and instead compensated us with leftover PR box samples and invitations to fashion shows. Not only were we unpaid, but we were further demeaned and traumatized in the workplace. The fashion industry is famously one of the most toxic industries in the world. This makes sense when you consider that without financial validation of labor performed, and the security of a paycheck, people working in fashion have to prove their worth to one another by leveraging social capital and by selling their identity. In an industry that fails to pay garment workers for completed orders, where well-known stylists are still asked to work for “credit only,” and where consumers are taught that they can buy their way out of their insecurities, we would be delusional to think that the fashion dream would ever center our survival. Therein lies the problem. If fashion is but a dream, then the only people who can afford to thrive are those who never have to face reality.

We do not have the privilege of never waking up. We have bills to pay and college debt looming on the horizon. Is fashion not for us?

Our report explores the themes that have arisen from the data collected during our two-year study of fashion’s unpaid internship structure. We have interviewed 16 people across nine professions, we have read numerous books, and we have conducted multiple surveys to which a total of 191 people responded. We have also written papers defending our right to be paid for our labor because we cannot demand to be monetarily valued if we cannot ascribe worth to work. In the time that we have been researching this topic, we have each completed internships at a total of 10 different companies in five different cities. Our third and most recent internship was completed with Liz Ricketts, Director of The OR Foundation and Founder of the Sustainable Fashion Initiative (SFI), in summer 2020 during which we focused on synthesizing our research. Ironically, this last position spent researching unpaid internships was the first time that one of us was paid for an internship.

We Recommend:

The report ends with recommendations for the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) and for the educational institutions preparing fashion’s future designers, and for brands. We do not hold any one of these entities responsible, but all of them are guilty of perpetuating an unsustainable system. If a company requires free labor to operate, then that is not a sustainable company. If we want independent, human-scale designers to be successful (which we do) then we need to confront this fact. Too many brands accumulate impressive levels of followers, press mentions, and accolades only to go bankrupt because the fashion dream does not pay. By dismissing the topic of unpaid internships as petty or by justifying unpaid labor as part of the hazing-ritual of fashion, we avoid a greater reckoning. The dream was never within reach. Just as the mythology of the “American Dream” is built on exploitation for the benefit of the few, so too is the fashion dream. This fashion dream is not the future we aspire to.

If we are going to rebuild a sustainable, and by sustainable we mean inclusive, fashion industry then paying Interns seems like a good place to start.

Again, we do realize that many independent brands and startups cannot afford to pay interns a living wage. This is why we have asked that the CFDA work with small, sustainability-led, brands to support internship positions for disadvantaged students. In our recommendations for educational institutions we have also asked that schools do more to financially support disadvantaged students while also becoming vocal advocates against ‘Big Fashion’ as it is only by championing independent brands that schools can ensure there are enough jobs for their graduates. Too many design students operate with a scarcity mindset; the belief that there are more designers than there are jobs. This is only true because of the way ‘Big Fashion’ consolidates opportunities.

Solutions for brands:

In addition to the solutions mentioned above we recommend that brands be more transparent about their financials and if a brand is unable to pay a living wage we recommend a few alternatives including the following:

- Hold office hours once a month where students can sign up for one-on-one mentorship sessions. It is important that this time is set aside intentionally for this purpose.

- Offer students a percentage of sales for the garments / collections they contribute to. Nanushka’s Design for Life Mentorship Program is an excellent example of this.

- Partner with other brands, think tanks, scientists and circular technology developers to co-sponsor and co-train the next generation. Sustainability cannot be a competitive advantage so partner up and build the infrastructure and know-how together.

We also draw a hard line for brands. There are certain circumstances under which we believe unpaid internships are completely unacceptable regardless of company size. Those circumstances are as follows:

- Unpaid interns outnumber paid employees.

- Unpaid interns are required to work more than two full days a week or more than three days a week with limited hours.

- Unpaid interns are required to exceed six months in their position without pay.

- Unpaid interns are required to perform tasks that are essential to the financial stability of the company without any mentorship and/or tasks that are essential, but that no paid employee has the skill to complete.

- Unpaid interns are asked to work an irregular schedule that makes it impossible for them to find additional paid work.

For more on the problem and for more solutions please read the full report here and you can reach out to us on Instagram: @sfi_cincinnati or email us at: hi@sficincinnati.org